Curatorial Note

Of nostalgia, awe and a sense of dread

Artists maintain a complex relationship with nature. Nature, while being the ultimate reflection beauty as intelligent design, is traditionally not considered art itself. It is only the source of inspiration and subject matter for art, which has long been held to be essentially a product of human creativity. Nature is the work of God while art is our own humble attempt to mimic divine creativity. There is thus a clear distinction between the nature and art, the passive object (reality) and the creative subject (artist).

From Plato to Andre Bazin, art was long thought to be essentially mimetic or imitative of nature. The artists have attempted to imitate nature in various ways, of course. Some aimed at trompe l’oell while others are more keen on abstraction or a desire to reveal the hidden geometry of the things in nature.

The Enlightenment and Romanticist philosophers have thought that nature is more mysterious than it seems. There is so much that we do not know about it and probably never will (What Immanuel Kant calls the Noumenon is completely impenetrable to us). There seems to be an invisible force, a Spirit or Being that permeates nature and, being a part of it, the human unconscious.

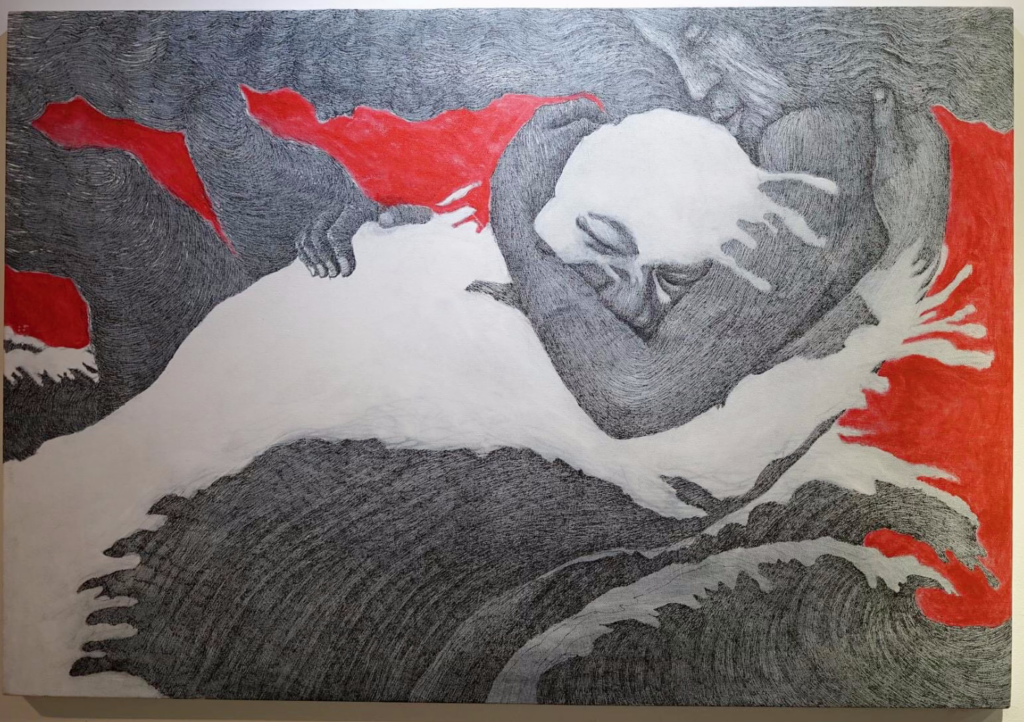

Friedrich Nietzsche has shown that this Spirit is far from being simply rational and that its work is not always orderly or intelligent. The Dionysian can be a force of madness and destruction. He must be alluding to Kant’s notion of the Sublime as something that evokes both awe and dread at the same time. Romanticist art is inspired by such musings of nature as both beautiful and violent.

This exhibit reflects this discourse on art and nature. The works of Jay Nathan Jore and Palmy Tudtud-Pe take on the contradiction of the Sublime, how the beauty of nature can be a source of nostalgia and solace but also a premonition, a reminder of inevitable decay, death or apocalypse (the end of the Antropocene). Josua Cabrera’s work echoes this sense of foreboding and vulnerability in the face of the violence of nature, which found expression in the local folklore that he alludes in both poetry and painting.

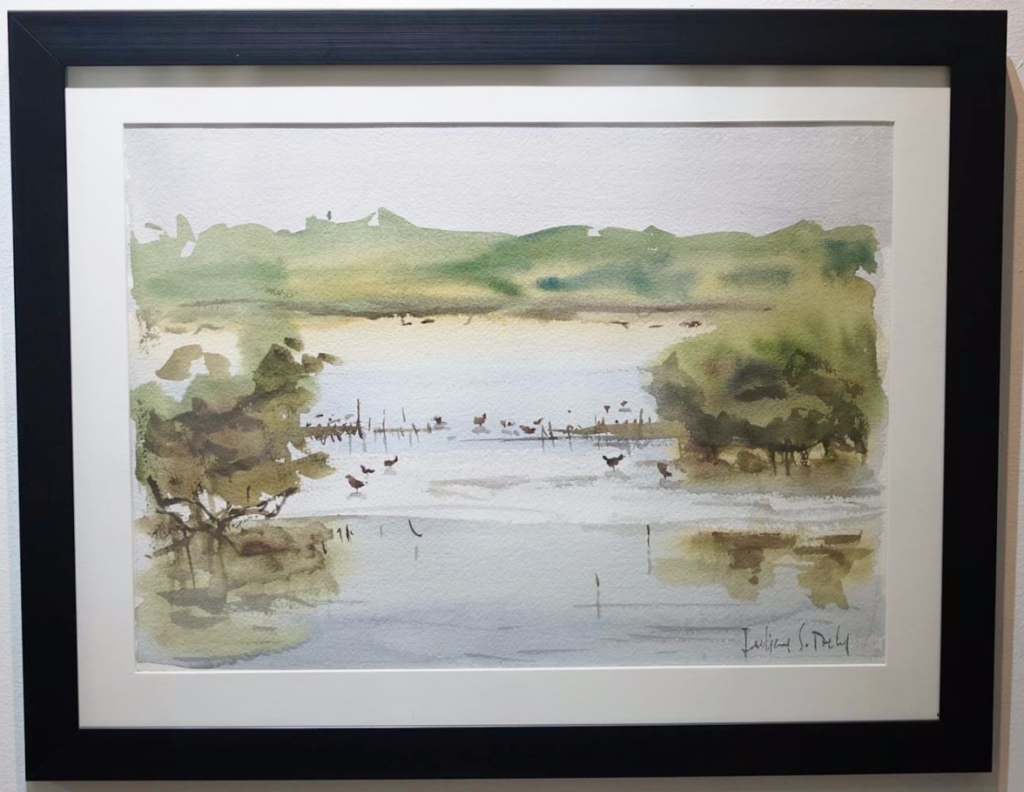

The diptych scrolls of Radel Paredes and Julienne Del Mar’s paintings also reflect this nostalgia for the idyllic, pastoral or paradise, a desire to keep the memory of nature as a source of joy and exuberance. But for both artists, part of this joy is the act of painting itself, of being able to play intuitively with form, or to tease viewers with visual wit.

And, in Palmy’s installations, even the convention of art as distinct from nature is interrogated as actual natural objects, in this case roses hanging upside down from dead vines pointing towards a mound of earth placed on the floor. Between these two installations of suspended roses is a painting of a vase of fresh roses placed on a pedestal and foregrounding another painting, this time that of a sunset. This is a parody of Platonic mimesis but also semiotic play as both the signifier and the signified are presented to the viewer in order to suggest yet another contradiction: permanence and impermanence, life and death.

Radel Paredes